ICE Score

The ICE Score is a prioritisation method for quickly comparing different ideas based on three factors: Impact, Confidence and Ease.

An ICE score is a variant of impact/effort estimation, with the addition of a confidence component. This is significant because it makes low confidence items less attractive and promotes the idea of performing additional research before jumping into implementing an idea. Unlike most other impact/effort estimation tools, an ICE score inverts the “effort” component turning it into “ease”, so it can be added or multiplied rather than used as denominator.

The ICE score method was invented by Sean Ellis and popularised in the book Hacking Growth. Conceptually, it’s similar to Impact Estimation Tables which predate it by several decades, but it is simpler and less formal than the older method.

How to calculate the ICE score?

Different authors propose combining the three metrics in different ways. Ellis and Brown suggest using a ten-point scale for each component, then averaging them to create the final score. Many online articles recommend simply adding the components. The downside of those approaches is that all three components have equal contribution, so an slightly easier item with very low confidence can win over a well researched item of medium complexity. In Evidence Guided, Itamar Gilad suggest multiplying the three components to reach the final score. The benefit of this approach is that low confidence scores have a significant impact on the outcome.

Assigning scores

The scoring of Impact, Confidence, and Ease can be highly subjective, depending on the individual’s perspective, knowledge, and biases. Predicting impact, in particular, is a very difficult problem, as final outcomes might be affected by a range of factors outside of the control of the delivery team (such as competitor actions, consumer preferences, global financial trends and similar). Tools such as Product Opportunity Assessment questionnaire and the QUPER model can help with predicting the impact component.

To reduce the subjectivity and increase consistency, Gilad suggests using predefined scales.

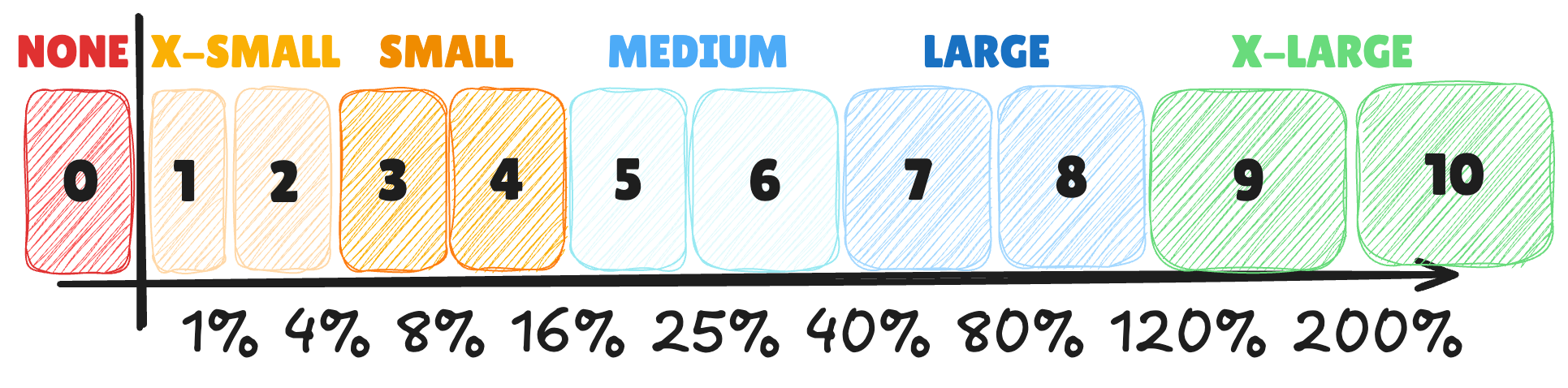

For impact, Gilad suggests picking one of the Key Result metrics from the current OKR objectives, and then mapping it to 0-10 based on predefined tiers of expected metric change. For example, 0.1-0.9% expected improvement gets impact score 1, 15%-25% produces impact score 5, and improvements over 200% get an impact score of 10. The number should be validated against past ideas, assessment and fact finding, simulations or tests and experiments.

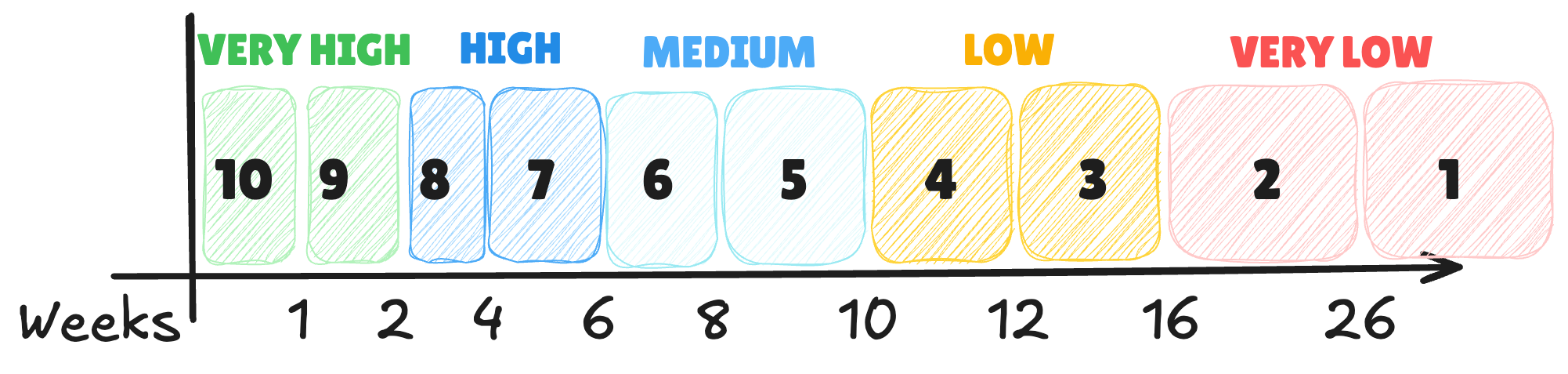

Similarly, for ease of implementation, Gilad suggests setting up a predefined scale measured in weeks. For example, anything longer than 26 weeks gets a score of 1. Items that would take 8-9 weeks to implement get a score of 5, and items that can be done in less than one week get a score of 10.

For scoring Confidence, Gilad suggests using his own model called the Confidence Meter, with a scale from 0.01 (self-conviction) to 10 (launch data). In effect, this means that estimates relying on self-conviction get divided by a factor of 100, and estimates tested with users get multiplied by a factor of 5 to 10, creating several orders of magnitude of difference and encouraging people to perform activities that increase confidence before proposing an idea.

Focus on the discussion, not on the result

According to Gilad, the goal of ICE is “to facilitate a structured discussion”. The purpose of assigning specific numbers “forces us to be more deliberate and clearer”, according to Gilad, but he also points out that people can just use None/Low/Medium/High or T-Shirt sizes for similar results.

Note that the numbers should always be the result of a discussion, and not a single person just inventing the numbers. The discussion around scoring individual components might end up being more beneficial than the actual final score. In that way, the ICE method is a good reminder for design teams and product managers to discuss the topics of impact and ease and evaluate their confidence in the conclusions.

ICE Score variants

There are many variants that try to complement the ICE method with additional factors. Some examples are RICE (Reach + ICE), or DICET (Dollars/revenue + ICE + Time-to-money). However, ICE seems to be the most popular as it strikes a balance between effort and usefulness. More complicated methods might produce seemingly more precise results, but would not necessarily be more accurate. For example, estimating reach, revenue or time to money is as difficult to do as with impact, and the final result might also be affected by many external factors making such estimates wildly inaccurate.

Applicability and limitations

The ICE formula is best used for relative comparisons and simple back-of-the-napkin analysis. It is particularly useful for quick comparison and triage, such as screening ideas to include in an Idea Bank.

This method is quick and rough, but because the scores are subjective and relative, it is best used for relative comparisons instead of an absolute score that is valid for a longer duration. Note that the ICE formula suffers from mathiness, so it should not be taken as accurate or included as a component in aggregate scoring and estimates across a large set of items.

The method is relatively simple and looks at each idea independently, effectively ignoring dependencies between ideas, which can lead to a skewed prioritization if some aspects are prerequisites for others. It may lead to a short-term focus, where items that are easier and have a quicker impact are prioritized over more impactful but difficult initiatives.

Another big limitation of this method is that it reduces complex ideas to just three dimensions, potentially oversimplifying the decision-making process and ignoring other relevant factors like risk, strategic alignment, and long-term value.

Learn more about the ICE Score

- Evidence-Guided: Creating High Impact Products in the Face of Uncertainty, ISBN 978-8409536399, by Itamar Gilad

- Hacking Growth: How Today's Fastest-Growing Companies Drive Breakout Success, ISBN 978-0753545379, by Sean Ellis, Morgan Brown (2017)

- ICE Scores – All You Need to Know by Itamar Gilad