Persona Spectrum

A Persona Spectrum is an extension of the classic product management concept of a user persona, allowing for a wider discussion about the contexts in which users take on the role of the persona.

A Persona Spectrum provides a framework for discussing a range of interaction needs by the different types of users who might take on the role of a specific persona, especially in the context of inclusive design and accessibility. Although the model originated in interaction design, it is also useful for widening product reach and unlocking growth by identifying underserved categories of users.

The Persona Spectrum model originated at Microsoft, and was popularised in their Inclusive Design Guidebook. Kat Holmes, one of the authors of the Guidebook, expanded on Persona Spectrums in her book Mismatch.

According to Holmes, the persona spectrum helps to both consider a “continuum of ability” but also to helps with “understanding why people across that spectrum want to access that solution”.

Identifying design mismatches

A core idea when creating a persona spectrum is to consider that a design idea might not be a good match for different groups of real people represented by an abstract user persona due to their abilities. By identifying subcategories of the persona, we can identify different types of mismatches between the design idea and people’s abilities, and then review and adjust the design accordingly.

For example, when considering the colour scheme and contrast between different elements of a user interface, we might consider potential mismatches between the design and people’s abilities. Elderly users or people with poor vision might experience mismatches with low-contrast design that has high information density. Colour-blind people might experience mismatches with designs using certain colour-schemes even at low information density. People who are temporarily in a very bright environment (such as a beach) might not be able to use a low-contrast design easily, even if they have no physical eyesight impairments. People who work in a high-stress environment with lots of distractions might not be able to quickly spot and react to information presented without sufficient contrast.

A Persona Spectrum is usually presented as a horizontal range, starting from the group that has the biggest mismatch, and continuing across to the right with different categories of people in descending order of mismatched interactions. The people on the spectrum are connected through the motivations and usage goals. When designing a spectrum, Holmes insists that it’s important to understand what motivates a person to use a solution:

It’s important to understand what motivates a person to use a solution. Rarely it is a purely functional reason, like knowing the identity of a sound. More often they are motivated by some more universal human need, like an increased sense of independence or creating an emotional connection.

– Kat Holmes

The goal of a persona spectrum is to make such potential mismatches clear so that the stakeholders, designers and product managers can make a conscious decision how broadly to support different people on the spectrum.

Solve for one, extend to many

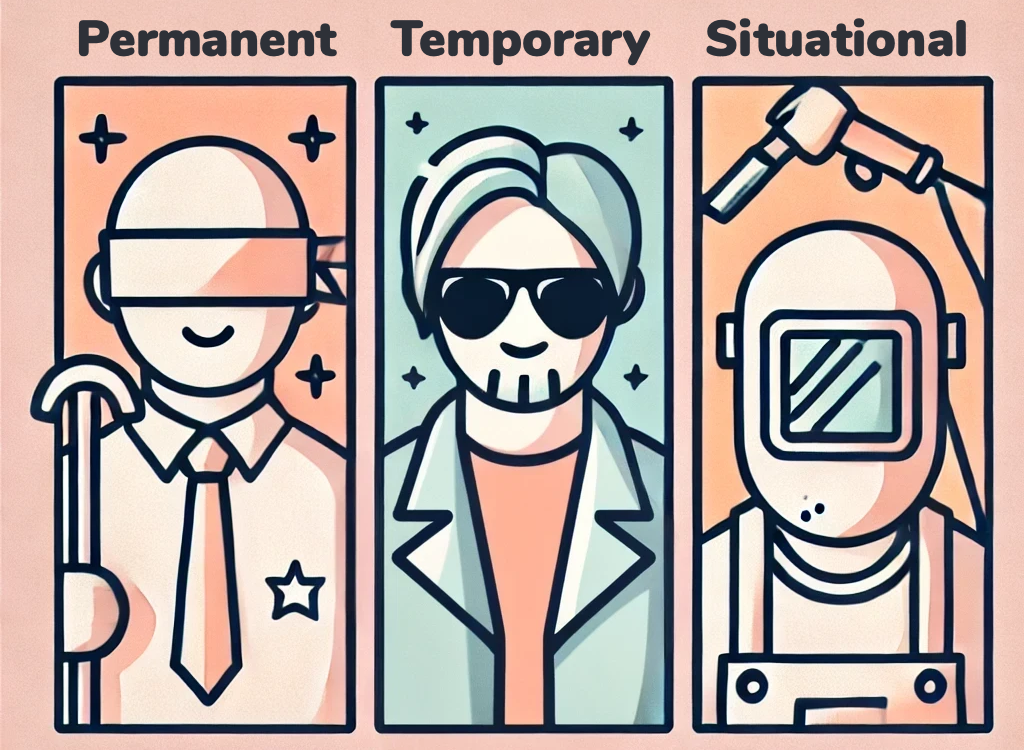

The typical progression on the persona spectrum ranges across three categories of ability/technology mismatches: Permanent, Temporary and Situational.

- Permanent mismatches are caused by ongoing conditions, such as amputations or congenital disabilities, that result in a long-term impact on ability. In the contrast example above, elderly or colour-blind people would fit into the permanent category.

- Temporary mismatches are caused by short-term impairments, which affect ability for a limited period. Someone suffering from an eye injury or wearing sunglasses might just temporarily have a mismatch with low-contrast solutions.

- Situational mismatches are context-dependent limitations, where the environment or task creates temporary constraints, such as the work setting or the external environment. People sitting on a beach under bright sunlight are situationally impaired, as are the people who work in an environment with lots of distractions.

One of the key uses of the persona spectrum is to design for one person, but then extend the solution across the spectrum. Holmes provides an example of closed captions and subtitles, that emerged as a assistive technology for deaf people. Captions and subtitles are now universally accepted by lots of users who do not have a hearing disability, ranging from people who are temporarily in a noisy place (such as a bar or an airport), to students trying to watch a video lesson in a foreign language. This means that designing a solution that fits a spectrum gives it a much broader reach than just designing for a single user persona.

The Microsoft Inclusive Design Guidebook highlights the potential for considering a persona spectrum using statistics across the range upper arm disabilities:

- Permanent: Roughly 26,000 individuals in the U.S. live with conditions such as arm amputations.

- Temporary: Approximately 13 million people have temporary disabilities, such as injured arms.

- Situational: About 8 million face specific situational challenges, like new parents carrying a baby or bartenders holding objects in one hand while working.

This implies that designing a solution that enables a product to be used with one hand doesn’t help just the 26,000 individuals with permanent disabilities, but it can ultimately make the product better for a broader audience of around 21 million people.

Considering the whole spectrum is important when designing solutions to understand why certain design affordance choices might be important. It may not be economically viable to change a product just to help 26,000 potential users, but addressing a potential market of 21 million might justify the investment in a more inclusive design.

Using a Persona Spectrum for product growth

A persona spectrum helps us to understand users and their challenges in different situations, so we can consider the design choices and trade-offs that might reduce mismatches.

Having a clear, focused user persona as a target is critical for early stage products, still looking for a product/market fit. (In the Five Stages of Growth terminology, a narrow persona is key for the Empathy stage).

However, blurring the persona definition and accepting some variety in the different groups of people who might fit into that category is important for growth. By considering potential mismatches and then expanding the solutions for a specific category to the whole range, products can cover a much wider potential group of customers. In particular, addressing temporary mismatches can help with the Stickiness stage of growth, as the product provides existing users in different contexts, so they are more likely to increase frequency or urgency of usage. Dealing with situational mismatches can help to address new but closely related categories of users, and expand the available market, important for later stages of growth.

Learn more about the Persona Spectrum

- Microsoft Inclusive Design Guidebook by Albert Shum, Kat Holmes, Kris Woolery, Margaret Price, Doug Kim, Elena Dvorkina, Derek Dietrich-Muller, Nathan Kile, Sarah Morris, Joyce Chou, Sogol Malekzadeh (2016)

- Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design, ISBN 978-0262539487, by Kat Holmes (2020)