Stakeholder Mapping

Stakeholder Mapping is the process of visualising the influence of various stakeholders on a product, in order to ensure that the needs of important stakeholders are considered for product planning, to manage and avoid risks arising from potential negative influence, and to gather the required political and organizational support for an initiative to succeed. Stakeholder analysis is an essential component of product development, complementing the insights gained from customer analysis, as it can help to ensure internal organizational support and help to identify various operational, financial, legal, and market-related risks.

- Key goals of stakeholder analysis

- The Power/Interest matrix

- The Mendelow Matrix (Power/Dynamism)

- The Freeman Matrix (Power/Stake)

- Who counts as a stakeholder?

Key goals of stakeholder analysis

In A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management, Freeman and Mcvea credit the origin of the idea of stakeholder analysis to the work done at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) in 1960s. The concept of stakeholder analysis entered common management jargon in late 1970s, becoming a popular topic for academic research and business journals in 1980s. Many of the methods for stakeholder classification and analysis that are still commonly used were discovered and documented in that period.

SRI argued that managers needed to understand the concerns of shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, lenders and society, in order to develop objectives that stakeholders would support. This support was necessary for long term success. Therefore, management should actively explore its relationships with all stakeholders in order to develop business strategies.

– R. Edward Freeman and John F. Mcvea, A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management

In Strategic Management of Stakeholders, Ackermann and Eden list three key goals for stakeholder management:

- Identifying who the stakeholders really are in the specific situation (rather than relying on generic stakeholder lists).

- Exploring the impact of stakeholder dynamics; acknowledging the multiple and interdependent interactions between stakeholders

- Developing stakeholder management strategies; determining how and when it is appropriate to intervene to alter or develop the basis of an individual stakeholder’s significance

Stakeholder mapping can directly help with all three issues. Various methods for visualising stakeholder groups both assist with identifying potential stakeholders and suggesting how to effectively work with them.

The Power/Interest matrix

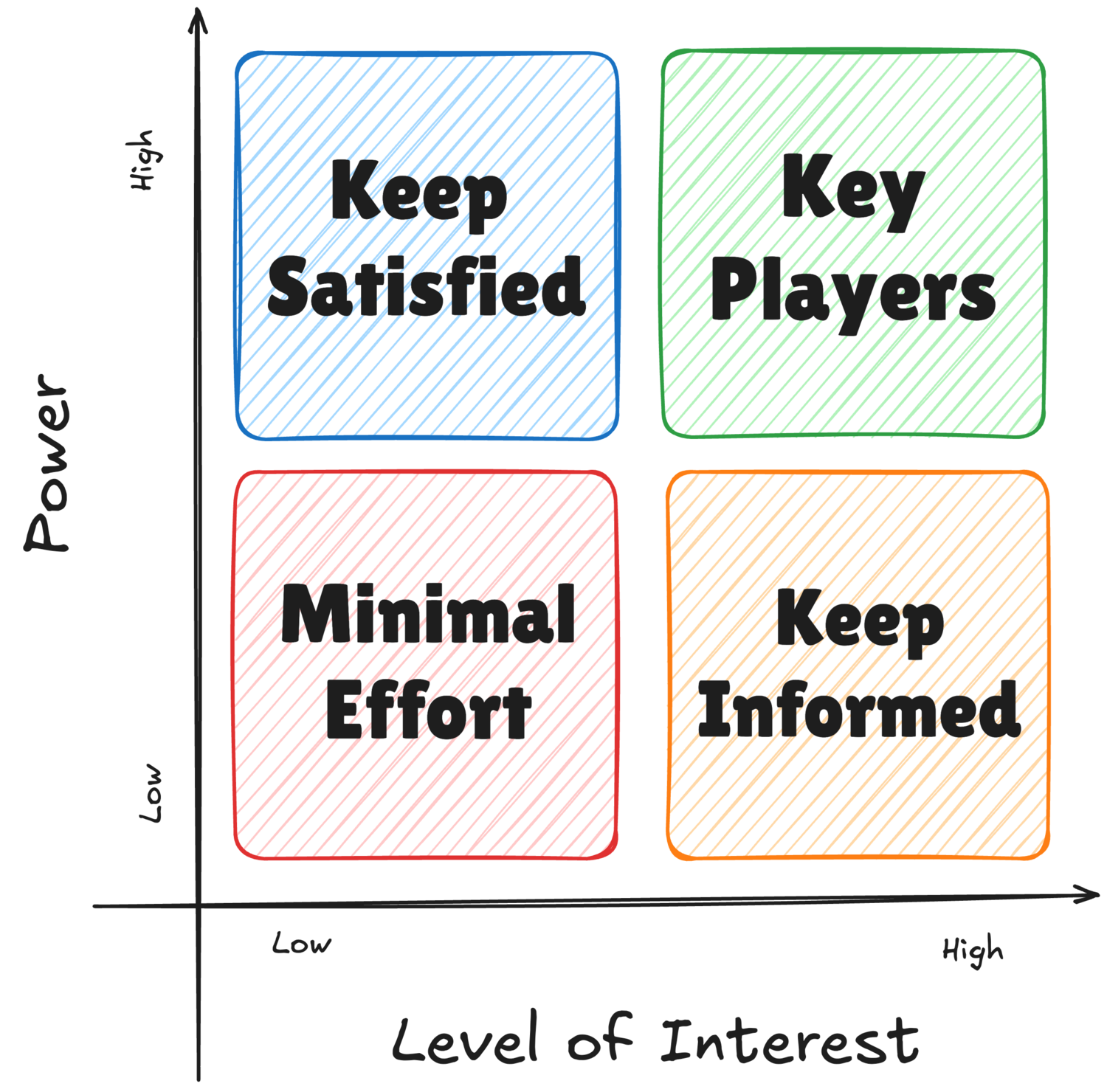

One of the most popular methods for visualising stakeholder groups is a matrix based on two factors: stakeholder power and interest.

This model is useful as it helps to identify different relationships and engagement strategies with groups of stakeholders:

- High power/High interest: Engage these stakeholders fully when formulating and evaluating new strategies. These stakeholders are the key players.

- High power/Low interest: Consider likely reactions of these stakeholders to specific events and ensure their support. These stakeholders are generally passive, but can shift to key players unless if they feel threatened or their interest changes.

- Low power/High interest: Address the needs of these stakeholders largely through information. These stakeholders can be crucial allies.

- Low power/Low interest: These stakeholders are not immediately important, but may change into one of the other categories over time, so they may need to be engaged in some low effort way to perform maintenance.

Tracking down the exact source of this matrix has proven a bit tricky, as most online and printed sources incorrectly attribute it to A. L. Mendelow or R. Edward Freeman. Both Freeman and Mendelow presented models similar to the Power/Interest matrix, but the earliest documented source we could find for this specific visualisation is the book by Johnson and Scholes. In the 2nd edition, published in 1993, Scholes and Johnson present the Power/Interest matrix as a “powerful development” of the earlier Mendelow matrix, without citing any specific source for the change.

The Mendelow Matrix (Power/Dynamism)

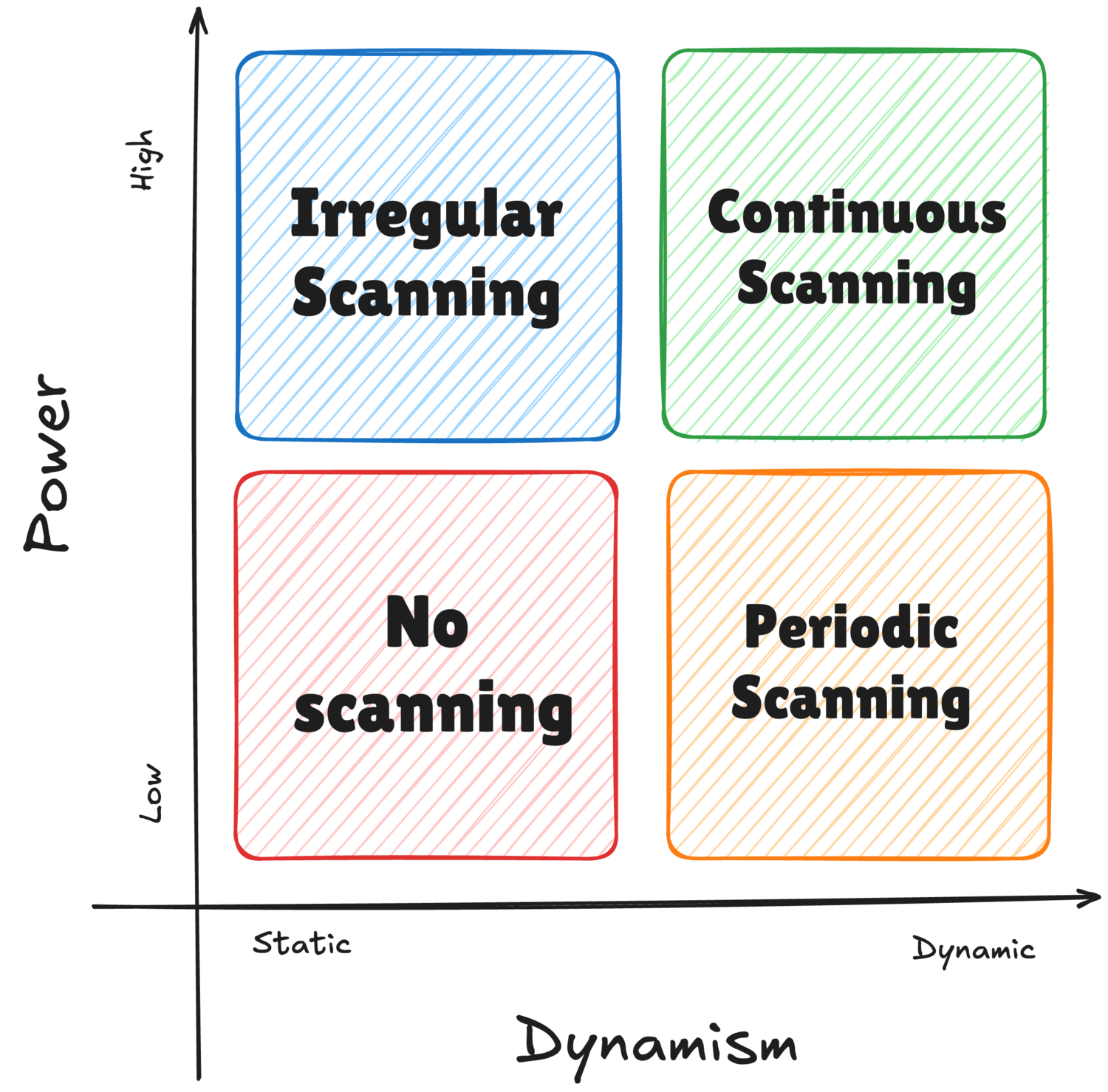

A. L. Mendelow was the first to suggest focusing stakeholder engagement efforts so that an organization can “predict the impact of environmental events surrounding the powerful stakeholders”. In order to determine the various outputs required by those stakeholders, Mendelow suggests a technique called “Environmental Scanning”, based on the earlier work of Francis Aguilar. In Aguilar’s terminology, the term “Environmental” refers to the wider system around the organization, not to the more contemporary meaning of climate/the natural world. Scanning refers to a process of periodically searching for signals, evaluating trends and situational changes, taking inspiration from radar scanning. Mendelow’s 1981 paper Environmental Scanning – The Impact of the Stakeholder Concept is the initial inspiration for pretty much all the later stakeholder mapping models.

Among the various stakeholder categories, Mendelow suggests that it’s critical to identify key individuals (“without whom the organization would cease to exist–the key employee, the sole supplier, the major customer […] people for whose goods or services there are no substitutes”), then focus efforts on “scanning these environments pertaining to the more powerful stakeholders.”

According to Mendelow, power provides “the ability to restructure situations”. Crucially, according to Mendelow, the power of a stakeholder can change over time (“The basis on which stakeholders possess power relative to an organization is liable to change depending on the impact which the stakeholder’s environment has on the stakeholder’s basis of power”). Choosing the right way to engage with stakeholders depends on both their power and how their situation is likely to change. Mendelow categorises stakeholders into 4 categories based on those two factors.

- Static/Low power: no scanning. The stakeholders are weak, and their situation changes slowly and is unlikely to materially be different in the future.

- Static/High power: irregular scanning. Ad-hoc engagement, potentially using historical information, repeating the process whenever environmental changes happen.

- Dynamic/Low power: periodic scanning, reassessing the effect of the stakeholders based on updated information.

- Dynamic/High power: continuous scanning, to ensure that problems are avoided and that potential threats are countered in time.

Evaluating stakeholder power

Mendelow suggests that power may come from authority, influence, the possession of resources and the availability of alternatives. To determine stakeholder’s power categorisation, Mendelow suggests rating each category of power on the scale of 1 to 5 (e.g. 1 would represent a supplier with plenty of competition, 5 would be a sole supplier for the availability of alternatives), then adding the scores in each category. Once all the stakeholders are scored for power, the mean of all the scores becomes the threshold they need to cross to fall into the High Power category.

Evaluating stakeholder dynamism

To evaluate dynamism, Mendelow suggests considering two factors:

- The frequency with which a stakeholder category is taken into consideration in decision making

- the frequency with which factors such as technology and economical changes influence the stakeholder’s power base.

Both of these factors should independently be ranked from 1 to 5, and the final score is the sum of the two factors. Similarly to power, the mean score of all the stakeholders is the threshold between low and high dynamism.

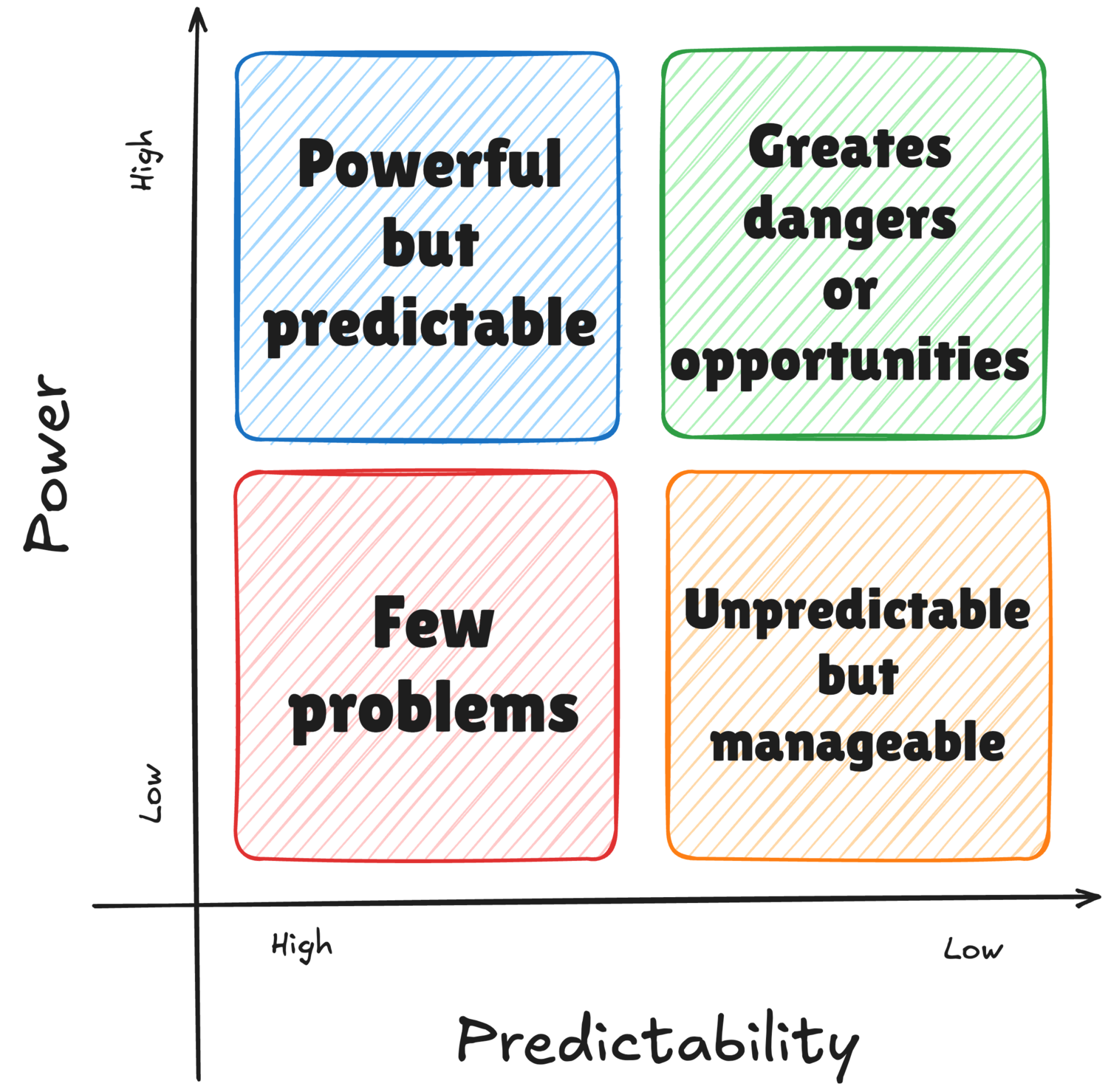

Scholes/Johnson alternative: Power/Predictability

The idea of evaluating dynamism is problematic both from the perspective of objectively estimating it, and from the perspective of being a separate factor in stakeholder evaluation. Factors such as technology and economical changes can be important drivers of dynamism, but the underlying issue influencing stakeholder engagement are not the changes themselves, but the fact that stakeholder power influence can shift. In Exploring Corporate Strategy, Scholes and Johnson changed the Dynamism axis to consider predictability of stakeholder actions, providing perhaps a more complete picture.

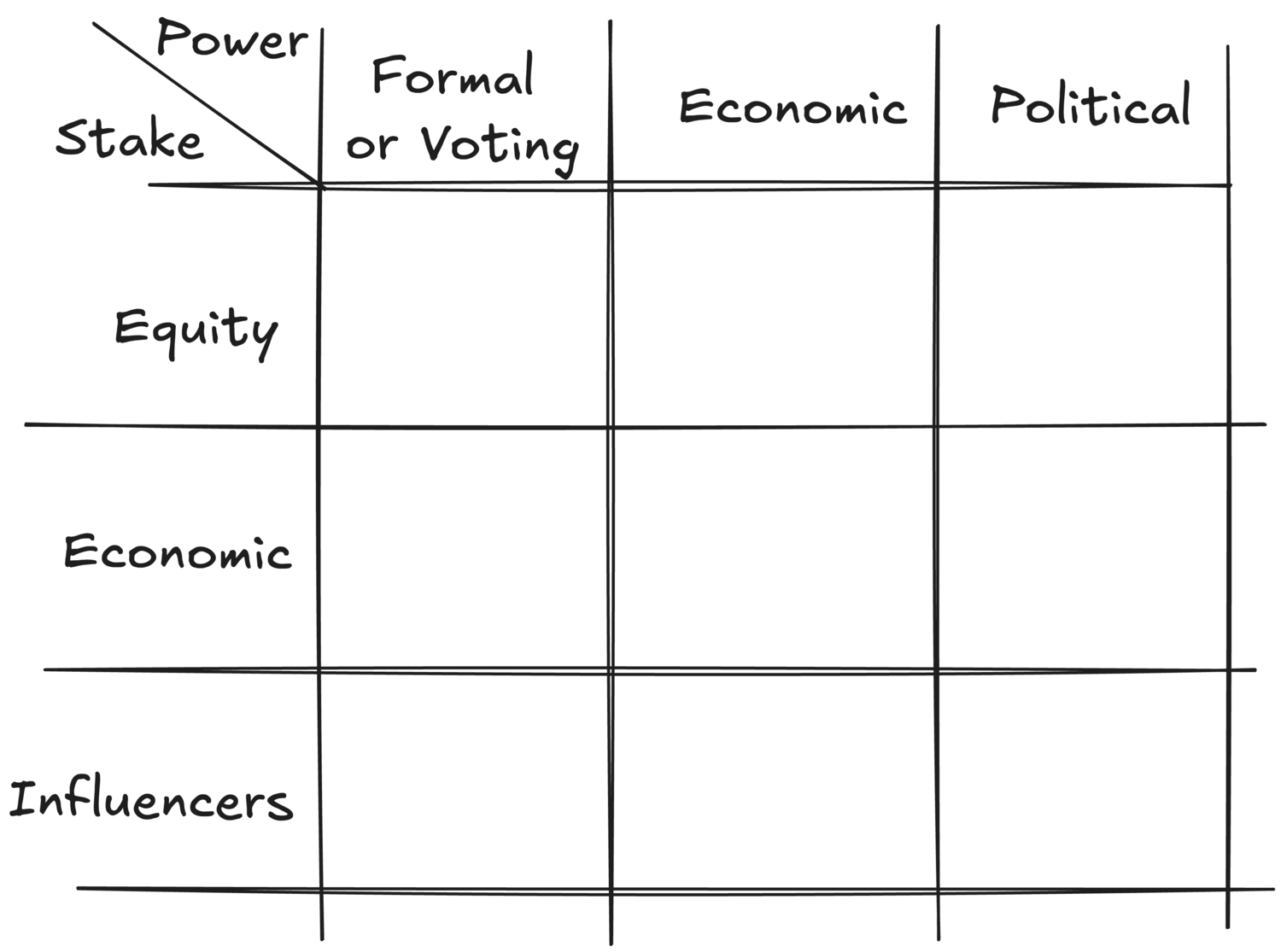

The Freeman Matrix (Power/Stake)

R. Edward Freeman modified the Mendelow matrix in his 1984 book Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, but breaking down different categories of power. Freeman takes a much wider view of stakeholders (see the section on Who counts as a stakeholder), considering people with direct or indirect influence and power, and providing for a third category in between each options which mostly revolves around monetary influence. For example, on the power scale, Freeman suggests that people with formal/voting power (e.g. shareholders) have the largest influence, followed by people who can financially impact an initiative (customers, sponsors, budget holders), followed by people who can mostly influence through opinions (advocacy groups, experts, advisors).

Instead of dynamism or predictability, Freeman suggests refining the power clusters based on how the mapped initiative impacts stakeholders (Freeman calls the second category interchangeably interest or stake). Noting that there’s no “hard or fast criteria” to apply, Freeman suggests that there’s a range from holding an “interest in the firm” to being a “kibbitzer”, or “someone who has an interest in what the firm does because it affects them in some way, even if not directly in markeplace terms”. Between those two categories, Freeman adds a third that is affected in the marketplace (e.g. competitors, lenders).

There are no specific engagement methods suggested for any of the categories in Freeman’s book, but the matrix is instead used as a brainstorming or mapping tool to consider all the different categories of stakeholders.

Who counts as a stakeholder?

R. Edward Freeman popularised the term stakeholder in his 1984 book Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. In paper published a year before the book, Freeman and Reed provide two definitions of a stakeholder:

- The wide sense of stakeholder: any group or individual who can affect of an organization’s objectives or who is affected by the achievement of an organization’s objectives.

- The narow sense of stakeholder: Any group or individual on which the organization is dependent for its continued survival.

Mitroff and Mason defined stakeholders as those who have a “vested interest in the problem and its solution”, particularly “those who depend on the organization for the realization of some of their goals, and in turn, the organization depends on them in some way for the full realization of its goals”. They propose seven approaches to generating a list of stakeholders (note that this is related to discovering stakeholders for public policy making, so not all would apply to products):

- imperative (people who publicly revealed their interest or defiance)

- positional (people who occupy important formal positions, both internal and external)

- reputational (people who have an informal stake, and can usually be identified by those with positional influence)

- social participation (people who participate in activities related to the objective)

- opinion-leadership (people who have an informal influence, and can usually be identified by those with positional influence)

- demographic (people who are impacted)

- organizational (people in an important relationship with the key organization, such as suppliers, employees, competitors, regulators etc).

Mendelow expands on Mitroff and Mason’s work in his 1981 paper, focusing more on stakeholders for commercial organizations. Combining various previous taxonomies, Mendelow suggests that the main categories for stakeholders are:

- Shareholders

- Government

- Customers

- Suppliers

- Lenders

- Employees

- Society

- Competitors

Mendelow suggests that the organisation’s stakeholders are the ones judging its effectiveness, based on different types of outputs, and that an organization needs to engage stakeholders by creating those outputs based on the stakeholder power and dynamism (see the Mendelow Matrix).

Learn more about the Stakeholder Mapping

- Environmental Scanning -- The Impact of the Stakeholder Concept, Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Systems by Aubrey. L. Mendelow (1981)

- A logic for strategic management, Human Systems Management, Volume 1, Issue 2 by Ian I. Mitroff, Richard O. Mason (1980)

- Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, ISBN 978-0521151740, by R. Edward Freeman (1984)

- A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management by R. Edward Freeman, John F. Mcvea (2001)

- Strategic Management of Stakeholders, from Long Range Planning, by Fran Ackermann, Colin Eden (2011)

- Stockholders and Stakeholders: A New Perspective on Corporate Governance, from California Management Review, Volume 25, Issue 3 by R. Edward Freeman, David L. Read (1983)

- Scanning the business environment by Francis Joseph Aguilar (1967)

- Exploring Corporate Strategy, ISBN 978-0132963930, by Gerry Johnson, Kevan Scholes (1988)