Tog's paradox

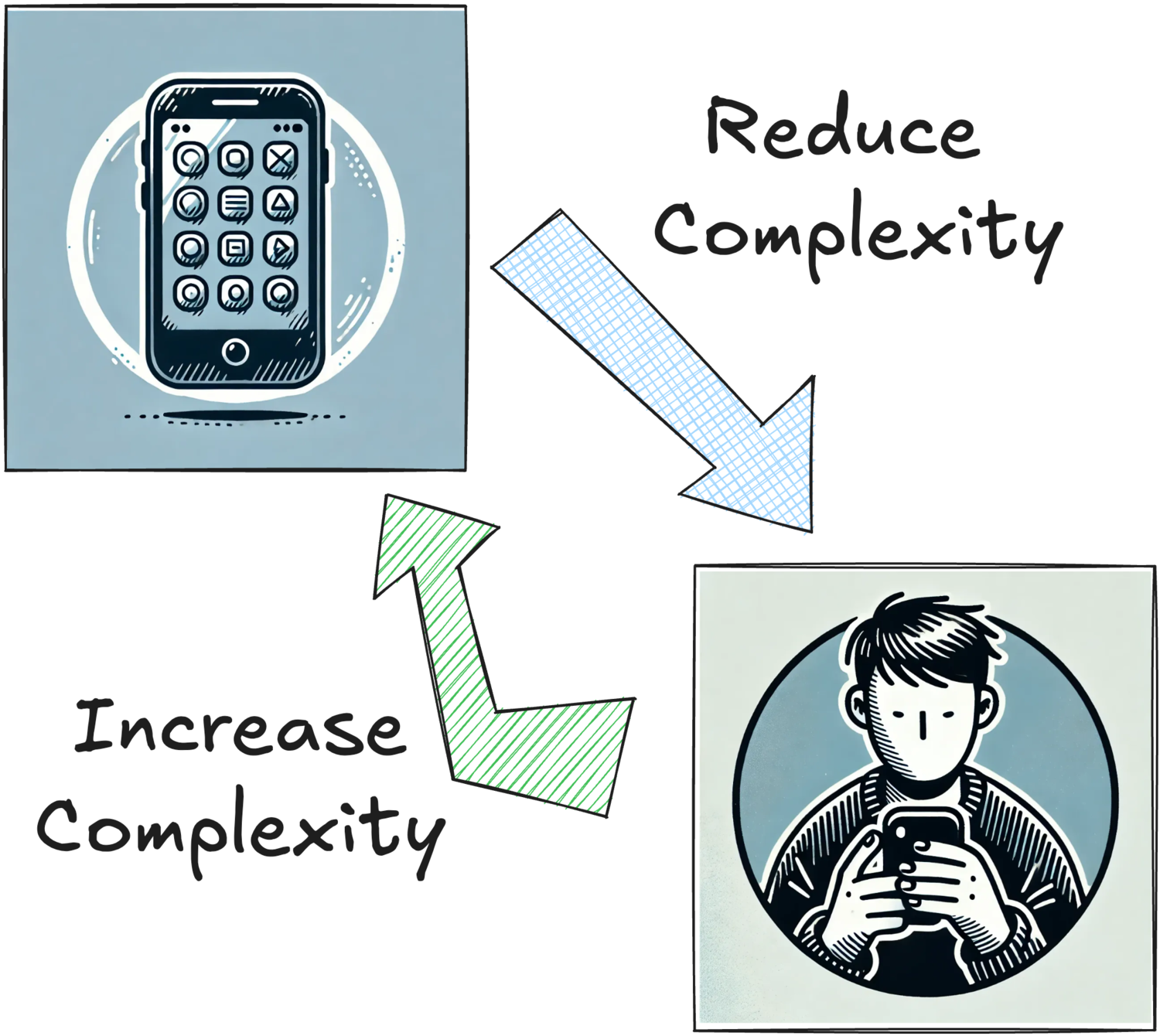

Tog’s Paradox (also known as The Complexity Paradox or Tog’s Complexity Paradox) is an observation that products aiming to simplify a task for users tend to inspire new, more complex tasks. It’s one of the key reasons for the symptom of requirements changing after delivery in enterprise software products, and for feature creep in consumer products. Tog’s Paradox also explains why it’s futile to try to completely nail down requirements for a software product, as the product itself will have an impact on the users, causing them to demand new functions.

[when] we reduce the complexity people experience in a given task, people will take on a more challenging task.

– Bruce Tognazzini, The Complexity Paradox

- Loophole in Tesler’s law

- Examples of Tog’s Paradox

- Tog’s paradox explains why requirements always change

Loophole in Tesler’s law

Bruce Tognazzini formulated the paradox as a loophole in Tesler’s Law, which states that inherent complexity in a user task does not change (but it can be shifted from a user to an application or the other way around). Tognazzini suggested instead that the task complexity does not stay the same, but increases.

The argument follows Tognazzini’s previous observation, called Tog’s Law of Commuting (published in the 1995 book Tog on Software Design), which suggests that users have a specific amount of time to complete a task, and if they can finish the work sooner, they will take on more work to fill the available time.

People will strive to experience an equal or increasing level of complexity in their lives no matter what is done to reduce it.

– Bruce Tognazzini, The Complexity Paradox

In spirit, Tog’s Paradox is similar to Jevon’s Paradox (which loosely states that technological advances which improve the efficiency of using a resource tend to lead to increased demand) and Parkinson’s law (which states that work expands so to fill the time available for its completion).

Examples of Tog’s Paradox

Tog’s Paradox is highly visible in enterprise software development, where attempts to streamline workflows often lead to more complex requirements over time. For instance, a CRM system designed to automate customer interactions might initially focus on basic functions like managing contacts and tracking communication history. Once users experience the efficiency gains from these core features, they begin requesting more sophisticated tools—such as integrations with other software, advanced reporting, or analytics to further optimize their work. Each new feature brings added complexity to the system, requiring not only more robust infrastructure but also additional training and support. This mirrors Tognazzini’s idea that making tasks more efficient encourages the demand for additional use cases, driving the complexity of the software.

Tog’s observation is also evident when software increases user productivity but leads to expanded scope in responsibilities. Consider an HR platform that automates payroll and performance management, freeing up HR staff from routine tasks. HR teams will need to justify what they do the rest of the time, and may use this newfound capacity to take on more strategic roles—such as employee engagement or talent development initiatives—which eventually demands additional software functionalities. The software that initially saved time ends up accommodating these new, more complex tasks, reinforcing the idea that saved time often gets filled with more work, creating an ongoing cycle of increasing complexity. This phenomenon is common in enterprise software, where solving one problem often leads to the creation of new, more intricate challenges.

The law also plays out in consumer applications. Social media platforms like Instagram or Twitter/X are another clear example. Initially designed to provide simple ways to share photos or short messages, these platforms quickly expanded as users sought additional capabilities, such as live streaming, integrated shopping, or augmented reality filters. Each of these features added new layers of complexity to the app, requiring more sophisticated algorithms, larger databases, and increased development efforts. What began as a relatively straightforward tool for sharing personal content has transformed into a multi-faceted platform requiring constant updates to handle new features and growing user expectations. Tog’s Paradox is evident here, as simplifying one aspect of the communication and sharing often drives demand for other, more complex ways of sharing content.

Tog’s paradox explains why requirements always change

Tog’s Paradox reveals why attempts to finalize design requirements are often doomed to fail. The moment a product begins to solve its users’ core problems efficiently, it sparks a natural progression of second-order effects. As users save time and effort, they inevitably find new, more complex tasks to address, leading to feature requests that expand the scope far beyond what was initially anticipated. This cycle shows that the product itself actively influences users’ expectations and demands, making it nearly impossible to fully define design requirements upfront.

This evolving complexity highlights the futility of attempting to lock down requirements before the product is deployed. No matter how thorough the initial planning, the reality is that users’ experiences with the product will inspire new use cases and deeper needs. The product’s initial efficiency gains create a feedback loop, where users seek more capabilities and push for new features and workflows. These second-order effects suggest that software development must embrace flexibility and continuous iteration.

Ultimately, Tog’s Paradox underscores that requirements gathering and user research are not one-time events, but part of an ongoing process. Attempting to fully specify requirements beforehand fails to account for how the product itself will influence user behavior and expectations. To truly meet users’ needs, products must be built with the understanding that the needs will change due to user interactions with those same products, the complexity will grow, and user demands will evolve, often in unpredictable ways. Recognizing this dynamic is key to building successful products that remain responsive and relevant over time.

Tog’s Paradox has significant implications for user experience design, particularly in how complexity impacts usability and user satisfaction over time. As products evolve and add features in response to user demands, the original simplicity and ease of use can degrade, leading to a more complex and sometimes overwhelming interface. This presents a core UX challenge: balancing the need for added functionality with maintaining an intuitive and accessible user experience.

Learn more about the Tog's paradox

- The Complexity Paradox by Bruce Tognazzini (1998)

- Tog on Software Design, ISBN 978-0201489170 (1995)